The latest news right now in the video game industry revolves around the title Black Myth: Wukong, which has broken the record for the most concurrent single players on Steam.

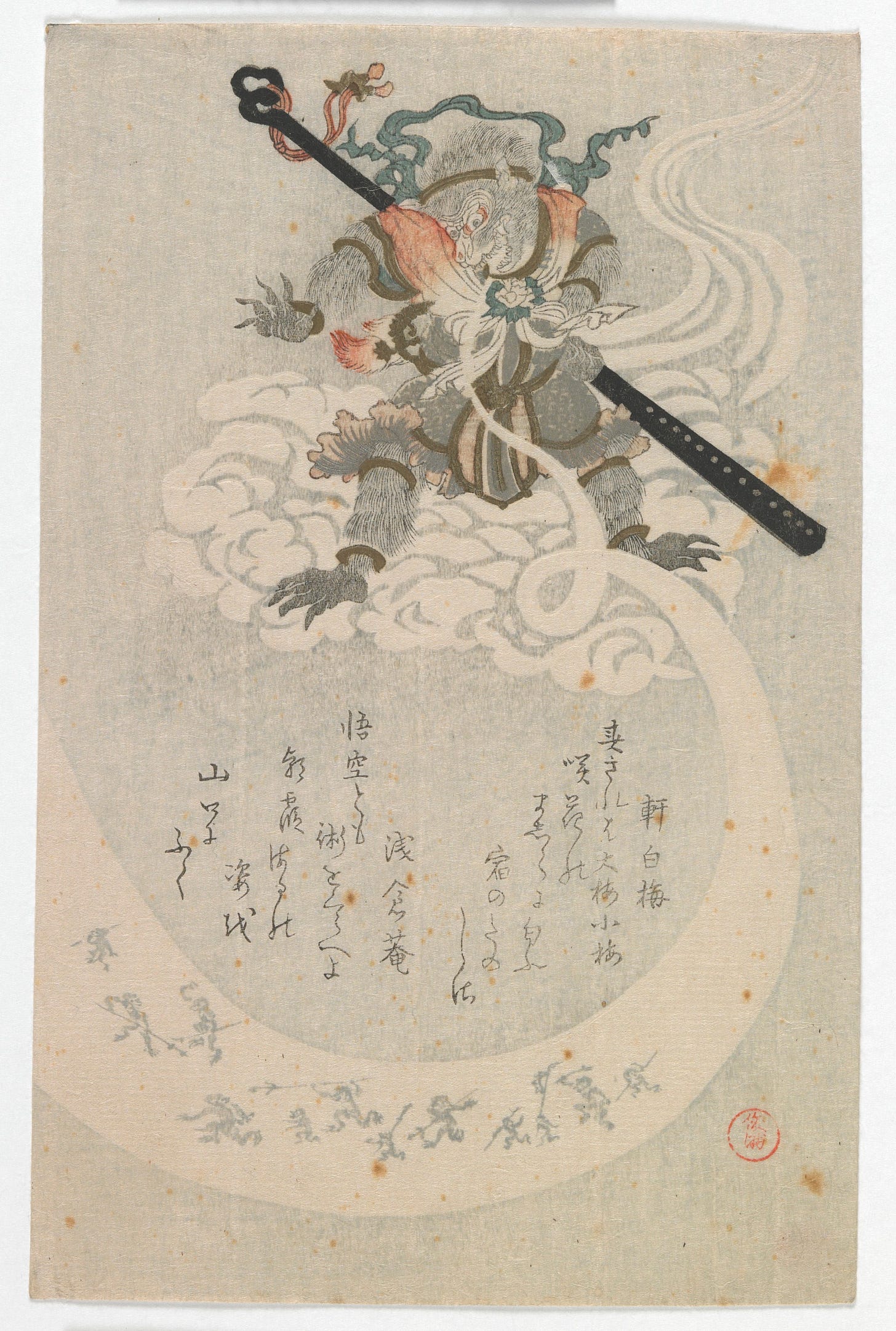

It looks really great — I haven’t played it yet but hope to soon. As the title suggests, this video game is based on the Chinese legend of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. In the original lore (“Journey to the West”), Wukong embarks on a quest to India (“The West”) to retrieve Buddhist scriptures, making both friends and enemies along the way. You may also have heard of Sun Wukong in other media, most notably under a different name — Son Goku from Dragon Ball:

Indeed, The Monkey King mythology has inspired many notable adaptations. We will take a look at some of them, and I’ll discuss why there should be more emphasis on historic Asian intellectual property (IP).

Adapting a Legend

Regarding The Monkey King’s copyright, which originates from China, the work is part of the public domain. Essentially, anyone can create derivative works based on the lore and claim copyright over the new resulting work. Chinese IP law is already quite complex and has long been known for difficult enforcement and insufficient protection, making this original source material a legal blessing.

Recently in the US, characters like the first incarnation of Mickey Mouse and Winnie the Pooh have also entered the public domain, leading to various non-Disney adaptations. I can’t say they’re good, but that’s the catch here. The idea behind the public domain is to foster creativity and innovation by providing access to legendary characters and stories.

Obviously though, there are practical restrictions. I will return to the public domain idea in a bit.

If anything, the original Monkey King story needs to be mentioned far more often beyond the Dragon Ball franchise. There are already many stories and characters inspired by Sun Wukong in Asia, in addition to Western adaptations from LEGO, Marvel and DC Comics.

The character of Sun Wukong himself is quite complex. He was punished by Buddha for causing disruption to the order, has superpowers like cloning and shape-shifting, and symbolizes martial arts. His mischievous yet heroic nature invites companions including Tang Sanzhang (monk), Zhū Bājiè (pig), and Shā Wùjìng (sandman), each of whom has inspired adaptations of their own.

Reflecting back at my childhood, I grew up with both Dragon Ball Z and a Korean cartoon series called “The Flying Superboard (날아라 슈퍼보드)” by Heo Yeong-man. The Flying Superboard, a modernized adaptation of The Monkey King, was a smash hit achieving the highest TV viewership of any animated series with 42.6% in 1992—a record that holds today. This incarnation still performs well and apparently, a K-drama adaptation may be on the way.1

Speaking of Korean content, I was reminded of this K-pop banger from last year:

Interestingly, the original Korean title is actually “Sun Wukong/Son Ogong/손오공,” with the international title and subtitle being “Super”. Therefore, the proper song title is “손오공 (Super).” The chorus even begins with “Feels like I turned into SONOGONG”, and the dance choreography pays homage to Goku of Dragon Ball Z. I’ve linked the timestamp above for your convenience.

It turns out The Monkey King is actually everywhere, much like his cloning powers - appearing in film, anime, theater, art, music, and video games.

Stories in the Public Domain

I believe we should be thinking more about the older IP originating from Asia— its histories, myths, fantasies, and legends.

Let me get back into the public domain idea with an example.

One of the more complex, yet successful Asian IPs is Godzilla, which has developed a cult following over decades. While it’s not a historic myth, global audiences enjoy watching monsters smash things. Given the success of Godzilla films in both the East and the West, I looked into whether the Japanese phenom is in the public domain. It’s actually quite complicated; there’s a distinction between the Japanese and the American adaptations and their respective laws.

Once copyright expires, the work enters public domain. In the US, the duration of copyright in media is as follows:

For works created on or after 1/1/1978: Life of the author + 70 years

For works created and published or registered before 1/1/1978: 95 years from date of publication

For works created but NOT published or registered before 1/1/1978: Same as 2), but can be extended to 120 years from date of creation if work is not published during author’s lifetime

For works that are made-for-hire, anonymous, or pseudonymous: 95 years from date of publication or 120 years from date of creation, whichever comes first

That’s quite a bit of rules and exceptions. For Godzilla, the original Japanese film incarnation (1954) is expected to enter the public domain in the US in 2050. However, we can anticipate the Japanese production company behind it, Toho Co. Ltd., to be relentless in enforcing its IP rights, as Japanese copyright laws are more complex. Additionally, copyright is distinguished from trademark law, and Toho will continue to enforce all trademark rights related to Godzilla in commercial use scenarios. So, don’t mess with stories and characters that have clear stakeholders.

Fortunately there’s other notable Asian stories already in the public domain, like the Yeti, The Golden Bat, Haemosu, and Cao Cao. I think there are plenty of opportunities for game developers and filmmakers to create derivative stories and capitalize on existing IP, as long as proper research is done and respect is given.

Overall, I think adapting The Monkey King lore into a next-generation console video game was a great idea—and long overdue. Video games set in Asia have been very popular in recent times; perhaps we just needed to look towards the past and be inspired.

Media Challenges

There is media controversy regarding Black Myth: Wukong, as game critics and reviewers were forbidden by its Chinese developer, Game Science, from discussing certain topics like COVID-19 or “feminist propaganda” in livestreams. I find this focus unfortunate, but fortunately the game has been a huge hit, with the controversy not affecting its positive reception on gameplay. Additionally, there is a separate controversy about the supposed lack of diversity in the game, as well as the developer’s previously misogynistic comments, which have led to backlash from members of the gaming community.

The gaming experience is something that differs for everyone. Since video gaming aims to be inclusive for all, we should expect a range of opinions and reviews on a well-developed game. I think that navigating this conversation can be challenging as social issues increasingly intersect with storylines and characters. To what extent should developers consider to fan and critic feedback when adapting existing IP into a well-developed game?

We can likely expect more Chinese game developers to make global waves with quality content, such as Phantom Blade Zero. Controversy and media coverage will inevitably follow, but that is to be expected. Perhaps this will lead to more in-depth conversations about how global consumers should best approach complex social issues that surround quality gaming.

For the time being, let’s celebrate the wins while continuing to consider the challenges in adapting well-known IP.

Thanks for reading! I can’t wait to play Black Myth: Wukong soon.

One of my favorite video game franchises from Japan — Yakuza/Like A Dragon —is coming as a live-action TV series on Amazon Prime. I’m not sure how great it’s going to be but my fingers are crossed. There are right of publicity issues that’s left some spin-off games up in the air, and I think this will be interesting to tackle in a separate piece.

Summer is almost over!

-Wooseok Ki (Wooski)

A unrelated K-drama titled “A Korean Odyssey” aired in 2017, which is based on The Monkey King lore as well.