My friend and dance teammate SJ once ranted, “Oh that guy is a huge biter. He rips off dance routines from famous people [pretending he made them].”

Well what’s he gonna do about it? I guess public or private criticism like the above.

Maybe an open confrontation and an invitation to settle out via freestyle dance battle.

Unfortunately, that didn’t pan out. Would’ve loved to see it.

The State of the Copyright Law

I find the concept of dance copyright intriguing yet peculiar - suing someone for infringing upon music, lyrics, or images seems relatively easier and more legally supported compared to pursuing dance copyright infringement.

In today's pop culture, elements like dance choreography by pop artists, short-form dances on TikTok, and hip-hop dance sequences or battles captured on video encounter significant challenges. There's a lack of robust legal precedent to navigate these areas, other than those involving ballet productions or yoga. Dancers often resort to public criticism and social media for support rather than relying on rigid copyright law or modern court interpretations for strong protection.

In the U.S., the Copyright Act (“CRA”) provides in Section 102(a)(4) copyright protection in:

“pantomimes and choreographic works” created after January 1, 1978, and fixed in some tangible medium of expression.

They really love fixed and tangible. Make sure everything is recorded on video.

Throughout the above guide from the United States Copyright Office (“USCO”), there is also an emphasis on:

The dancers’ skill level

Pro, amateur, or hobbyist? What kind of portfolio or career?

The dance’s purpose, whether to entertain others but not for own enjoyment

In front of an audience? Teaching a class? Flashmob? Social expression?

The choreography’s composition of moves

Is there a story or theme?

How intricate are the moves in isolation, and in succession?

Already, you may have some thoughts on these many considerations mandated by the CRA. I thought dancing was for everyone to enjoy, but this is quite strict.

Some of what’s NOT protected:

Commonplace movements / gestures / spelled-out letters

Social dance (ex: salsa, breakdancing) or simple routine

Ordinary and athletic movements

Exercise routines / yoga / feats of physical skill or dexterity

Some types of compilations

Aerobics or yoga

“A complicated routine consisting of classical ballet positions or other types of dance movements intended for use in a fitness class”

Examples given - classical ballet or the fitness dance, huh.

I then wonder, where would modern dance choreography routines (especially those of global artists, one-off workshop classes, K-pop, etc.) fit in when considering only the extremes mentioned?

To Boo or Sue

You may have heard of recent lawsuits surrounding the video game Fortnite’s “emotes” feature, in which characters animate popular dance moves from pop culture (ex: The Carlton, Backpack Kid’s Floss, Running Man). There wasn’t much progress for creators that sued. The lawsuits against Fortnite developer Epic Games had been dropped for now, due to copyright registration requirements imposed by the US Supreme Court (“SCOTUS”) in an unrelated case.1

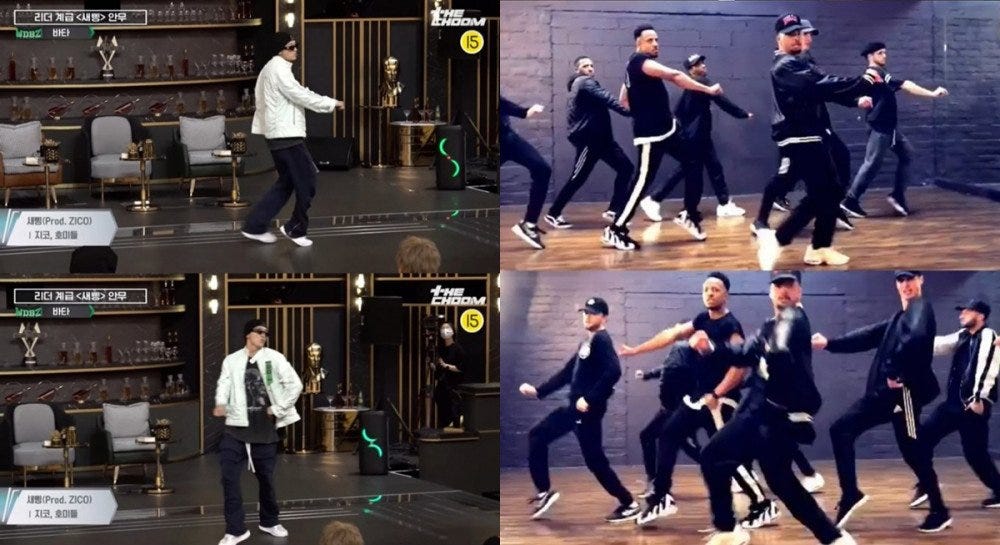

But take a look at the video below:

This is Kyle Hanagami, a veteran dancer who has choreographed for the likes of Justin Bieber, J.Lo, and BLACKPINK, as well as many projects and global workshops. In the video above, there are numerous technical moves forming the 4-count sequence from the choreography, which has been adapted as a Fortnite emote without Hanagami's permission. Hanagami had already registered the full choreography with the USCO in 2017.

Even if you’re not a pro dancer, you can see that the side-by-side comparison of the dance sequence is VERY similar, if not identical.

In the Kyle Hanagami v. Epic Games, Inc., et al (2023) litigation, the district court (= Round 1) dismissed the lawsuit on the ground that “a number of individual poses” are not copyrightable and the "two-second combination of eight bodily movements" were not protected.

Upon Hanagami’s appeal, the appellate 9th Circuit court (= Round 2) fortunately held that there were indeed substantial similarities between the two dances in question. It also held that the district court erred in dismissal just because the emote was “short and a “small component” of the overall choreography. I want to specifically shed light on the below from the 9th Circuit:

What is protectable is the choreographer’s selection and arrangement of the work’s otherwise unprotectable elements. The panel held that “poses” are not the only relevant element, and a choreographic work also may include body position…transitions, use of space, timing, pauses, energy…The panel concluded that Hanagami plausibly alleged that the creative choices he made in selecting and arranging elements of the choreography…were substantially similar to the choices Epic made in creating the emote.

We’re finally heading in the right direction in 2023. Dance choreography should not be judged on its duration or simplicity, nor should it be narrowed down to undermine its intricacy. The focus should be on which and how the elements comprise the coherent whole, and therefore any part of the sequence - whether it’s a pose, position, pause, etc. - should still be viewed as the choreography itself.

But as we saw with Round 1, there are still obstacles. Round 2 reversed and remanded, which means Round 1 must try this case again. For the time being, the copyright protection of modern dance choreography is still in limbo.

I’ll be monitoring this case closely in 2024, and I hope you’ll follow along with me.

Digital Age Considerations

Today in the age of short-form content, the goal of the creator is to captivate the audience’s attention span as quickly as possible.

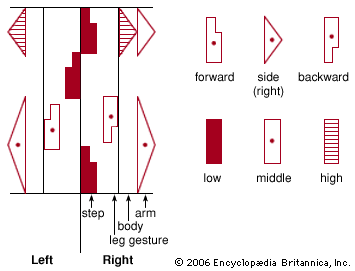

Fortunately, initiatives exist to bridge the gap between the creative process and rapidly evolving digital technology. In 2019, renowned choreographer JaQuel Knight, known for creating the iconic dance to Beyonce’s “Single Ladies”, collaborated with a nonprofit organization to formally codify his work—akin to creating a music score - using Labanotation. He successfully registered his commercial choreographic work with the USCO, with David L. Hecht serving as counsel2.

Afterward, Knight partnered with Logitech to support BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) dancers and creators in officially registering and legally safeguarding their work. Keara Wilson, a dancer who had created the TikTok Savage dance challenge in 2020 below, can now license her choreography for financial compensation and claim official credit.

It’s especially important to recognize that dance choreography builds on the work of Black culture and that proper credit is due.3

There’s no official statistic, but imagine the sheer volume of short-form videos involving dance in some way.4 Dance challenges have become a marketing staple for many hip-hop and K-pop artists. These are frequently adapted into emotes for video games like Overwatch, Fortnite, and Roblox, sometimes without obtaining permission from the original creators. Whether a dance originates in a teenager's bedroom or a professional studio, it's crucial to acknowledge and credit the original creator properly. Legal protections ensure creators receive credit and financial compensation for their creative works.

If there’s an easier way to legally safeguard dance choreography in the digital age, I’m certain all dancers would greatly benefit from it.

OR just maybe, we could all give proper credit and have a heightened degree of respect and understanding for the creative process.

Biting & Respect in Dance Culture

Back to my friend SJ. What’d he mean by biting in dance?

The quick answer - copying a dance move from someone else without permission or prior communication.

Additionally, you cannot sue someone for biting, unless they had the balls to rip off an original choreographic work in its entirety. Then we’d go do down the litigious rabbit hole above but remember that currently, individual dance moves cannot be copyrighted, only the entire choreography can. As I noted above, what actually may constitute copyrightable choreography is still being decided. Courts are presently less likely to view a sequence of consecutive dance moves as copyright infringement.

But I bring this up here because it may shed light into how we should think about originality and creativity going forward.

According to breakdancing pioneers Asia One and Rokafella, copying a dance move could stem from:

Idolization and paying respect/homage

Challenging oneself to execute the move

The move widely used to become fundamental

Unaware of the original or who made it

Bad faith

Hence, creativity is an ongoing process and we draw inspiration from those we pay attention to, sometimes whether we intended to or not. I resonate with Rokafella here:

We're all influenced by each other because we're a society-based diaspora and we react to good vibes. We're excited by creativity because it communicates intelligence and we prefer to be around inspiration. Otherwise, life feels stagnant and flavourless. The important thing is while doing all that to carve out your own niche.

Let’s promote good vibes, positive influence and inspiration whenever we can.

On a more optimistic note - we are finally seeing more active movements to legally safeguard copyright in dance, especially as to modern forms in the digital age. There’s probably more to come in 2024, but a personal shoutout to all the dancers, whether pro, hobbyist, or retired, in cultivating our creativity and continuing to stay inspired by the sources that surround us.

This is the last one for 2023! Thanks for reading this longer piece.

I had a lot of fun researching this topic and reflecting on my hobbyist dance competition days in high school and beyond. Personally, it’s bittersweet to think that a lot of us don’t dance anymore as we aged and shifted our focus to more immediate endeavors. However, I believe that our creativity is always there, ready to be manifested into whatever form we put our minds to.

This is my first legal-related piece on WooskiWrites. There is a lot of overlap between IP law and video games, so I reckon the next legal piece will explore that intersection again. But I’m always open to ears: connect with me on LinkedIn or @wooskiworks.

Have a great rest of the year!

-Wooseok Ki (Wooski)

Alfonso Ribeiro dropped his 2019 lawsuit against Epic Games, following an unanimous SCOTUS ruling requiring a plaintiff to register for copyright with the USCO (and be granted/rejected). Ribeiro hadn’t, but this doesn’t mean Ribeiro or other related plaintiffs can’t refile the claim again. Perhaps it’s worth waiting on how the Hanagami case below turns out.

David L. Hecht of Hecht Partners LLP also represents Alfonso Ribeiro, 2 Milly, Backpack Kid, and Kyle Hanagami in the aforementioned cases.

This type of modern dance choreography, also known as open-style, was previously widely known as “urban dance”. There was a collective community movement in recent years to boycott the term “urban” to pay greater respect and understanding to the pioneers of hip-hop and the Black creative community. More info in this STEEZY blog post.

Very broad, but #dance on TikTok yields 743.1B views.